Rage Against the Wind: The Markets Won’t Do What the OBBB Tells Them

Written by Emily Dwight and Professor Mark James

On his first day back in office President Donald Trump declared a “national energy emergency,” claiming the United States faces “a precariously inadequate and intermittent energy supply” threatening national security.[1] Six months later, he signed the “One Big Beautiful Bill Act” [2] (OBBB), fundamentally restructuring renewable energy tax incentives passed in the Inflation Reduction Act.[3]

There is only one problem: the emergency does not exist. Fossil fuel production reached record levels under the previous administration, grid reliability metrics contradict claims of systemic instability, and independent assessments found no evidence of a supply crisis.[4] As Columbia Law School scholars observed, “evidence suggests that current energy supply and price conditions simply do not constitute a national emergency.”[5]

The legal foundation for this emergency declaration is equally precarious. The Supreme Court warned in Biden v. Nebraska that emergency authority “does not empower the President to take actions free from statutory limitations.”[6] Legal scholars have categorized statutory emergency authorities, finding that many contain “specific statutory criteria or descriptions of ‘emergency’ circumstances which suggest that the declared energy emergency may not qualify.”[7] Even where agencies possess broader discretion, actions taken under a manufactured emergency could face “arbitrary and capricious” challenges under the Administrative Procedure Act.[8] Declaring an emergency, as the Columbia analysis noted, “regardless of fanfare and spectacle, does not give President Trump carte blanche to pursue his energy policy” when no true emergency exists.[9]

This disconnect raises a fundamental question: for what purpose? The OBBB imposes substantial costs on renewable energy development—wind and solar are the only sources that can be deployed at scale in the next few years—while failing to address genuine energy security concerns or reduce overall energy costs. The question is not whether we need more energy; we clearly do. The question is what resources can be deployed fastest and cheapest to meet surging demand. By every objective measure, that answer is renewable energy with battery storage, not new coal plants or extended operation of aging fossil infrastructure.

Perhaps the answer lies not in policy analysis but personal obsession. President Trump’s opposition to wind turbines predates his presidency by nearly two decades. Since 2006, he has waged a personal crusade against offshore wind development near his Aberdeen golf course in Scotland, filing multiple lawsuits claiming the turbines would destroy the property’s aesthetic value.[10] He lost every legal challenge, with UK courts ultimately ruling in 2015 that the project could proceed.[11] His objections were never grounded in energy policy analysis or grid reliability concerns—they were about the view from his golf course. His personal grievance has become America’s energy policy.

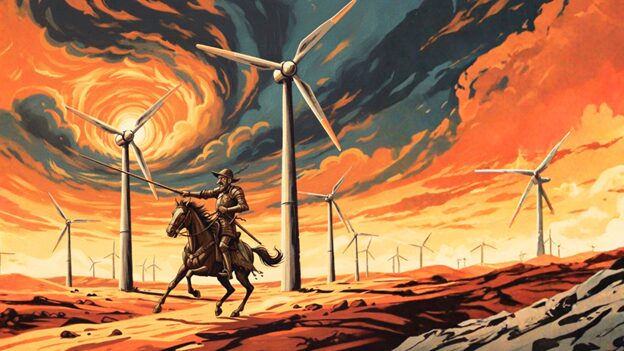

Like Cervantes’ knight-errant tilting at windmills, imagining them to be giants, the administration wages war against wind turbines while genuine challenges go unaddressed. The OBBB represents modern energy policy quixotism—an ideologically driven crusade against market forces, technological progress, and economic reality. The markets will not do what the OBBB tells them to.

American Energy Policy After the OBBB

The OBBB terminates tax credits for wind and solar projects placed in service after December 31, 2027, with a narrow exception for facilities beginning construction by July 4, 2026.[12] This compressed timeline creates extraordinary pressure: wind and solar projects starting construction in 2025 must be operational by 2029; those beginning after 2025 but before July 4, 2026 must achieve commercial operation by 2030; any project starting after that cutoff must be online by 2027—an incredibly short timeframe for utility-scale development.[13]

The IRA provided a decade-long framework that encouraged billions in capital commitments for manufacturing facilities, supply chain investments, and project development pipelines. The OBBB shattered that certainty overnight. Under the Inflation Reduction Act, technology-neutral clean energy tax credits were available for projects beginning construction through 2032, with a phaseout schedule extending into the late 2030s.[14]

The OBBB abandons technology neutrality for selective intervention that reveals the administration’s true targets. Energy storage, hydropower, and geothermal facilities retain credits phasing out in 2034. Fuel cell property gains a flat 30% credit without emissions requirements. Nuclear facilities receive enhanced credits through energy community bonuses.[15] This isn’t technology neutrality; it is energy favoritism. The “All of the Above” strategy has been replaced with the nightclub policy of “Yes, You, But Not You.”

The OBBB piles on more obstacles to the rapid deployment of solar and battery storage with the introduction of extraordinarily complex Foreign Entity of Concern (FEOC) provisions requiring applicants for the technology-neutral tax credits to demonstrate that their projects avoid prohibited “material assistance” from specified foreign entities.[16] The thresholds vary significantly by technology and year: wind and solar facilities beginning construction in 2026 must show that at least 40% of total direct costs come from non-FEOC sources, rising to 60% by 2030.[17] Battery storage projects face even higher thresholds—55% in 2026, escalating to 75% by 2030.[18] Solar energy components sold in 2026 must demonstrate 50% non-FEOC content, increasing to 85% by 2030.[19]

For technologies containing dozens of components manufactured across multiple countries, this demands supply chain visibility multiple tiers back through manufacturing processes. Industry analysts estimate compliance costs could add 15-25% to project development expenses, rendering marginal projects uneconomic even if credits remain technically available.[20]

A Multi-Front Assault: Beyond Tax Credits

The OBBB’s tax credit terminations represent only one front in a comprehensive, government-wide campaign. against renewable energy. Administrative actions have erected barriers potentially more devastating than loss of tax credit.

In August 2025, Interior Secretary Doug Burgum signed Secretarial Order 3438 requiring all wind and solar projects on federal lands to meet a “capacity density” threshold—essentially mandating that renewables generate as much energy per acre as nuclear or gas plants.[21] Since an advanced nuclear plant generates approximately 33.17 megawatts per acre while an offshore wind farm generates 0.006 megawatts per acre—a difference of 5,500 times—this standard functionally prohibits new wind and solar development on federal lands.[22] The comparison ignores fundamental differences in how these technologies operate: baseload plants run continuously at rated capacity, while variable renewables produce power when wind blows or sun shines.

Burgum’s order also requires his personal approval for all wind and solar projects on federal lands and waters through an “elevated review” process.[23] About 10% of new solar capacity under development sits on federal lands, along with critical transmission infrastructure.[24] Analysts have warned these projects “could be delayed or canceled if Burgum does not issue permits.”[25] The personal approval requirement creates a bottleneck where a single political appointee can effectively veto projects based on ideological preferences.

The constant attacks on offshore wind have the makings of a modern day Don Quixote tale. Even when repelled, the administration doubles down and comes back. On January 20, 2025, President Trump issued an executive order withdrawing all Outer Continental Shelf areas from new offshore wind leasing and imposing a moratorium on federal approvals pending “comprehensive review” with no timeline.[26] The order directs the Interior Secretary to assess “the ecological, economic, and environmental necessity of terminating or amending” of existing leases.[27] The administration has used this authority aggressively. In August 2025, it halted construction on Revolution Wind, an 80% complete project off Rhode Island, citing vague “national security concerns, before a temporary restraining order was issued that allowed construction to proceed.”[28] In November, BOEM received approval to remand a key permit issued to SouthCoast Wind.[29] On December 8th, a Massachusetts federal court judge ruled that the indefinite moratorium on federal approvals, imposed in the January 20th executive order, was arbitrary and capricious.[30] On December 22, 2025, the Department of the Interior issued stop-work orders for all five offshore wind projects currently under construction, citing again “national security concerns” argument that was unsuccessful against Revolution Wind.[31] Some of the paused projects were partially complete and already delivering electricity to the grid while another was expected to connect in the first quarter of 2026.[32]

The Department of Transportation’s withdrawal of $679 million in federal grants for port infrastructure supporting offshore wind construction at twelve different ports from California to Virginia.[33] Humboldt Bay, California lost over $426 million that would have transformed a struggling former timber port into a renewable energy hub.[34] Secretary Sean Duffy justified cancellations claiming “wasteful wind projects are using resources that could otherwise go towards revitalizing America’s maritime industry.”[35]

The cumulative impact is staggering. The Solar Energy Industries Association reports that over 500 solar and storage projects totaling 116 gigawatts—more than half of all power capacity planned through 2030—face political threats including permitting delays, grant cancellations, and regulatory uncertainty.[36] This includes 73 GW of solar and 43 GW of storage without all necessary permits. Eighteen states have over 50% of their planned generation capacity at risk, including Texas (which alone accounts for nearly 40% of at-risk projects), Virginia, Arizona, and Nevada.[37] Three of the top five affected states voted for President Trump in 2024.[38]

The Real Emergency: Meeting Soaring Electricity Demand

The reliability and affordability crises used to justify the emergency declaration crumbles under scrutiny. The administration’s framing blames the windmills for problems caused by aging coal plants reaching end-of-life. The North American Electric Reliability Corporation (NERC) identified regional capacity concerns but pointed to “planned thermal generation retirements” as the “primary contributing factor”—not renewable energy additions.[39] NERC specifically noted risks of “supply shortfalls” during late summer when “solar output diminishes earlier in the day”—a temporal mismatch that energy storage and transmission expansion could address.[40]

Decisions to keep aging coal plants online exacerbate rather than correct the problem. The Trump administration’s Executive Order on “Reinvigorating America’s Beautiful Clean Coal Industry” claims that “clean coal resources will be critical to meeting the rise in electricity demand due to the resurgence of domestic manufacturing.”[41] Yet a DOE emergency order, using its Federal Power Act Section 202(c) authority, keeping Michigan’s Campbell coal plant operating–when it was scheduled to retire 15 years before the end of its planned lifespan because it was uneconomic–encapsulates the disconnect between this rhetoric and reality.[42] The administration is addressing symptoms rather than causes, defend obsolete infrastructure rather than enable new resources. It treats planned retirement of aging fossil fuel plants as an “emergency” while accelerating termination of tax credits supporting technologies that could actually address capacity needs, all in service of “beautiful clean coal.”[43] Keeping the Campbell plant online cost ratepayers an extra $80 million between May 23 and September 30, 2025, more than $600,000/day.[44] If the DOE mandates that all the fossil fuel plants that are scheduled to retire by the end of 2028 remain online, costs to ratepayers could $3 billion per year.[45]

The administration is fighting physics and the passage of time in its efforts to bring back coal. Coal-fired electricity generation is a sector living on borrowed time. Competing technologies have gotten cheaper while coal has gotten more expensive. When the Bureau of Land Management held an auction for coal leases, it got one bid at less than a penny per ton. The BLM suspended two planned coal lease auctions.[46] The chivalrous-minded Don Quixote found similar results in his fight to return to the past. The future has made its decision about coal.

Yet an actual emergency looms: exploding electricity demand. Electricity consumption could grow 15-20% by 2030, driven by data centers, artificial intelligence, electric vehicles, and manufacturing reshoring.[47] Meeting this growth requires deploying new generation capacity at unprecedented speed—precisely when the administration is blocking the only technologies capable of rapid deployment.

The OBBB’s approach is predicated upon a fundamental logical flaw. The only technologies capable of rapid deployment at scale are solar and energy storage. Solar projects can be operational in 18-24 months; storage in 12-18 months. New natural gas combined-cycle plants require 3-4 years to construct, while turbine manufacturers now face wait times of 5-7 years for major equipment.[48] Nuclear plants require a minimum of 7-10 years to build, and that is the most optimistic timeline. Coal plants are not being built. Attacking the fastest-deployable resources while facing unprecedented demand surge exemplifies ideology triumphing over practical necessity.

The economics strongly favor renewables. Utility-scale solar now averages $24-$38 per megawatt-hour; onshore wind costs $24-$50/MWh.[49] New combined-cycle gas plants cost $45-$75/MWh, while maintaining aging coal plants can cost $80-$120/MWh when including environmental compliance.[50] Keeping uneconomic coal plants operational through emergency orders doesn’t make them economically viable—it simply forces ratepayers to subsidize more expensive generation when cheaper alternatives exist.[51]

American Competitiveness in the Global Energy Transition

The world that U.S. energy policy is trying to save exists only in the past. While the administration wages its crusade against wind and solar, the global energy transition accelerates.[52] China controls approximately 80% of global solar manufacturing, 60% of wind turbine production, and 75% of battery cell manufacturing—shares resulting from deliberate industrial policy spanning two decades.[53]

The OBBB’s immediate competitive damage stems from policy whiplash. The Inflation Reduction Act created a framework expected to persist for a decade, providing certainty for multi-billion-dollar capital commitments.[54] Companies made decisions to locate manufacturing facilities in the United States based on that expected stability. International competitors operating with stable policy frameworks gain decisive advantages: they can plan confidently for decades, while U.S. competitors face biennial policy uncertainties tied to election cycles.

Policy uncertainty increases risk-adjusted capital costs, making marginal projects uneconomic. Solar factories cost billions and take years to build; wind turbine manufacturing requires specialized facilities; battery gigafactories represent even larger investments. The Union of Concerned Scientists estimates the OBBB could result in “$150-200 billion in lost manufacturing investment over the next decade.”[55] This represents not just lost economic activity but foregone jobs, diminished technological capabilities, and reduced ability to compete in what will be one of the dominant industries of the 21st century.

The fundamental error in the OBBB’s logic is believing that U.S. policy choices can alter global energy trajectories. The transition will continue—driven by cost competitiveness, technology progress, and strategic positioning—whether or not America participates.[56] Solar and wind are the cheapest forms of new electricity generation in most markets worldwide. Battery costs continue declining on predictable learning curves. Countries pursuing energy independence increasingly choose renewables over imported fossil fuels. The question isn’t “will the energy transition happen?” but “will American workers, companies, and communities benefit from it?” Like Don Quixote inability to accept that the age of chivalry had ended, the OBBB imagines it can resurrect an energy system that market forces have rendered obsolete.

Energy Affordability: Understanding the True Drivers

The persistent claim that renewable energy increases consumer costs does not hold. Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory’s comprehensive analysis reveals that transmission and distribution infrastructure investments account for roughly 60% of rate growth over the past two decades, while generation costs including renewable integration contributed only 20-25% of rate increases.[57] The expensive components are the poles, wires, transformers, and substations—infrastructure needing upgrading regardless of generation source as equipment ages.

LBNL analysis reveals that in regions with significant renewable additions, wholesale electricity prices have declined due to the near-zero marginal cost of wind and solar generation. This “merit order effect” means renewables push higher-cost fossil fuel generation out of the dispatch order, reducing average wholesale prices.[58]

Understanding electricity costs requires distinguishing between rates and bills. Electricity rates measure price per kilowatt-hour; bills reflect total monthly cost, which equals rates multiplied by consumption. Bills can remain stable as rates increase if consumption decreases through energy efficiency improvements.[59] California has high rates (28 cents/kWh) but average monthly bills of $128, only slightly above the national average of $121, because per-capita consumption is among the nation’s lowest at 550 kWh monthly versus 877 kWh nationally.[60] Conversely, Louisiana has low rates (11 cents/kWh) but bills exceeding $135 due to high consumption from inefficient housing.[61] States with high renewable penetration don’t systematically have higher bills—they have different rate structures reflecting different infrastructure investment choices.

Critical Infrastructure Bottlenecks

Transmission infrastructure represents perhaps the most critical constraint. Building new transmission requires multi-state approvals, faces intense local opposition, involves complex cost allocation disputes, which combine to produce decades-long development timelines. Recent analysis reveals transmission investment runs at only $20-25 billion annually when $50-60 billion is required to support projected load growth and renewable integration.[62] Achieving 80-90% clean electricity by 2035 would require expanding transmission capacity by roughly 60%, representing hundreds of billions in investment.[63]

FERC Order 1920, issued in May 2024 with further clarifications in Orders 1920-A and 1920-B, is the most significant transmission planning reform in over a decade.[64] The order requires regional transmission planning to consider long-term needs over 20-year horizons and near-term reliability.[65] It mandates evaluation of transmission benefits for reliability, economic efficiency, and state public policy requirements.[66] Critically, Order 1920 establishes default cost allocation methodologies that should streamline planning processes by reducing disputes over who pays for new transmission infrastructure.[67] While implementation will take years, the framework could accelerate development of critical transmission projects within regional planning organizations.

A growing bottleneck does exist in getting resources connected to the grid. Over 2,600 gigawatts of generation capacity (95% renewable or storage), representing more than two times the size of the current U.S. generation fleet, sits in interconnection queues, with average wait times exceeding five years.[68] This backlog reflects fundamental dysfunction in how new generation connects to the grid. Projects that should take 2-3 years from application to operation routinely take 5-7 years or longer.

FERC Order 2023 attempts to reform dysfunctional interconnection processes through cluster studies processing multiple projects simultaneously and financial readiness requirements ensuring projects have secured financing before entering queues.[69] However, clearing accumulated backlogs will take years. FERC’s ongoing Notice of Proposed Rulemaking, in response to on DOE’s proposal directing it to standardize large-load interconnection rules. could reduce stress on the grid by clarifying the current, unclear large load interconnection process, including co-location and cost allocation rules.[70] Utilities that have implemented data center tariffs have seen considerable reductions in their interconnection requests as speculative projects have withdrawn.[71] Establishing clear cost allocation frameworks for these large loads will reduce the speculative behavior driving up connection requests and slowing development of generation projects intending to deliver power to the grid.

Meanwhile, Congress advances parallel efforts that could inadvertently undermine the administration’s anti-renewable agenda. The Simplifying Permitting to Enable Energy Development (SPEED) Act, which passed the House on December 18th, would codify key holdings from Seven County Infrastructure Coalition v. Bureau of Land Management.[72] The act would streamline NEPA review timelines and limiting opportunities for litigation delays.[73] Proponents frame the legislation as facilitating fossil fuel development, but the reforms would benefit any infrastructure project—including renewables. Given that solar and wind projects have 2–4-year development timelines compared to 7–10 years for new nuclear or coal plants, accelerated permitting would disproportionately advantage the very technologies the administration seeks to disadvantage. However, the SPEED Act faces a difficult path in the Senate over the Trump Administration’s attacks on offshore wind and renewables on federal lands.[74]

Conclusion: When Markets Won’t Follow Orders

The One Big Beautiful Bill imposes real, measurable costs visible across multiple dimensions. The purported benefits remain stubbornly elusive. The declared emergency was manufactured from mischaracterized data. Consumer electricity bills won’t meaningfully decline—rates are driven primarily by infrastructure investment, not generation costs, and the cheapest new generation, the resource that can reduce costs, is the resource being attacked. Energy security isn’t enhanced by reducing domestic renewable deployment while the U.S. remains a net energy exporter. Grid reliability problems aren’t solved by blocking the fastest-deployable generation capacity when actual emergencies involve surging demand requiring rapid capacity additions.

The OBBB puts a heavy thumb on the scale, explicitly advantaging fossil fuels while disadvantaging renewables through tax policy, administrative action, and regulatory barriers. But thumbs on scales don’t tip the scales of global energy transformation any more than Quixote’s lance could topple windmills. The transition will continue—driven by cost competitiveness, technological progress, and international competition. The markets will not do what the OBBB tells them. Solar and wind keep getting cheaper; batteries keep improving; countries keep choosing energy independence through domestic resources over continued import dependence.

The question facing American policy is whether the United States leads this transition, capturing economic benefits and shaping its direction, or lags while other nations seize opportunities American policy foolishly rejects.

The energy system we had is gone. We cannot resurrect it through policy alone. The economics have fundamentally changed—renewables are now the cheapest new generation in most markets. The physics have changed— technology is getting better and cheaper. The weather has changed – climate impacts are making extreme weather events more frequent, stressing grids designed for historical patterns. The politics have changed—renewable energy deployment creates jobs that cannot be offshored, lowers costs for consumers, and generates tax revenue for rural communities.

The path forward requires addressing the constraints this article has documented: transmission infrastructure that connects resources to demand centers, interconnection reforms that allow projects to reach operation in reasonable timeframes, and permitting streamlining as exemplified by the SPEED Act. There are additional challenges that this analysis has not fully explored—grid modernization enabling integration of distributed resources, market designs that properly value flexibility and resilience, workforce development programs, and mechanisms ensuring that American workers and rural communities benefit from the energy transition rather than being left behind. Changing our energy system is hard enough without having to overcome the pursuit of a system that no longer exists.

Cervantes’ knight-errant eventually recognized his delusions, acknowledging on his deathbed that he had been mad. The question is whether American energy policy will reach a similar recognition before opportunities are irretrievably lost—or whether the administration will persist in its crusade against wind turbines while the rest of the world moves forward. When the administration eventually confronts the actual emergency—meeting surging electricity demand in a climate-constrained world—it will discover that ideology cannot substitute for the resources it spent years attacking. By then, the opportunities squandered, and advantages ceded, may be irretrievable.

Author Bio:

Emily Dwight, a dual J.D. and MERL student at Vermont Law and Graduate School, serves as the Administrative Editor for Vermont Law Review Vol. 50 and Vermont Journal of Environmental Law Vol. 27. Emily is particularly interested in the legal frameworks governing the transmission system and the evolution of energy production. She looks forward to applying her background in energy regulation as an associate in Sidley Austin LLP’s Energy Practice following graduation.

[1] Exec. Order No. 14156, Declaring a National Energy Emergency, 90 Fed. Reg. 7537 (Jan. 20, 2025), https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/01/declaring-a-national-energy-emergency/.

[2] One Big Beautiful Bill Act, H.R. 1, 119th Cong. (2025) (enacted July 4, 2025).

[3] Inflation Reduction Act of 2022, Pub. L. No. 117-169, 136 Stat. 1828 (2022).

[4] U.S. Energy Info. Admin., U.S. Fossil Fuel Production Reached Record High in 2023 (2024), https://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.php?id=65445.

[5] Olivia Guarna & Michael Burger, Demystifying President Trump’s “National Energy Emergency” and the Scope of Emergency Authority, Climate Law Blog (Feb. 14, 2025), https://blogs.law.columbia.edu/climatechange/2025/02/14/demystifying-president-trumps-national-energy-emergency-and-the-scope-of-emergency-authority/.

[6] Biden v. Nebraska, 143 S. Ct. 2355, 2373 (2023).

[7] Guarna & Burger, supra note 5.

[8] 5 U.S.C. § 706(2)(A).

[9] Guarna & Burger, supra note 5.

[10] Kevin Keane and Aimee Stanton, How Trump’s loathing for wind turbines started with a Scottish court battle, BBC, July 29, 2025, https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/c15l3knp4xyo.

[11] Id.

[12] H.R. 1, § 4101 (amending 26 U.S.C. §§ 45Y, 48E).

[13] Id.

[14] Inflation Reduction Act of 2022, Pub. L. No. 117-169, §§ 13101-13902, 136 Stat. 1818 (2022) (codified in scattered sections of 26 U.S.C.).

[15] H.R. 1, § 4103 (amending 26 U.S.C. § 45Y to add nuclear energy community bonus credit).

[16] H.R. 1, § 4105 (adding new 26 U.S.C. § 48F establishing Foreign Entity of Concern restrictions).

[17] Hagai Zaifman et al., The “One Big Beautiful Bill” Act – Navigating the New Energy Landscape, Sidley Austin LLP (July 15, 2025), https://www.sidley.com/en/insights/newsupdates/2025/07/the-one-big-beautiful-bill-act-navigating-the-new-energy-landscape; see also Martin et al., Working Through The FEOC Maze, Norton Rose Fulbright – Project Finance News, July 8, 2025, https://www.projectfinance.law/publications/2025/july/working-through-the-feoc-maze/.

[18] Id.

[19] Id.

[20] Natl. Renewable Energy Lab., Foreign Entity of Concern Compliance Cost Analysis 28, NREL/TP-6A40-87234 (2025).

[21] U.S. Dep’t of the Interior, Secretary’s Order No. 3438, Managing Federal Energy Resources and Protecting the Environment (Aug. 1, 2025), https://www.doi.gov/document-library/secretary-order/so-3438-managing-federal-energy-resources-and-protecting.

[22] Id. (comparing advanced nuclear plant output of 33.17 MW/acre to offshore wind farm output of 0.006 MW/acre).

[23] Matthew Daly, Interior Secretary Burgum Must Personally Approve All Wind and Solar Projects, A New Order Says, Associated Press (July 17, 2025), https://apnews.com/article/burgum-trump-wind-solar-clean-energy-5f496ccc8b409edad853b35cc40728fb.

[24] Id.

[25] Id.

[26] Memorandum on Temporary Withdrawal of All Areas on the Outer Continental Shelf from Offshore Wind Leasing and Review of the Federal Government’s Leasing and Permitting Practices for Wind Projects, 90 Fed. Reg. 6,985 (Jan. 20, 2025).

[27] Id. at § 1.

[28] Clare Fieseler, Trump admin halts construction of nearly finished offshore wind farm, Canary Media, (Aug. 24, 2025), https://www.canarymedia.com/articles/offshore-wind/trump-admin-halts-construction-of-nearly-finished-offshore-wind-farm.

[29] Miriam Wasser, In Latest Anti-Wind Action, Trump Administration Moves to Revoke SouthCoast Wind Permit, WBUR (Sept. 19, 2025), https://www.wbur.org/news/2025/09/19/southcoast-wind-permit-seek-to-revoked-trump. For an updated offshore wind tracker, see Anastasia E. Lennon, Our offshore wind tracker: What’s new with wind projects off Massachusetts and beyond?, The New Bedford Light, (Updated Dec. 4, 2025), https://newbedfordlight.org/offshore-wind-tracker-whats-happening-to-massachusetts-projects/.

[30] Johan Sheridan, Judge overturns Trump order in favor of NY’s offshore wind, NEXSTAR News10.com (Dec. 9, 2025), https://www.news10.com/capitol/judge-strikes-down-wind-permit-pause/.

[31] Press Release, U.S. Dep’t of the Interior, The Trump Administration Protects U.S. National Security by Pausing Offshore Wind Leases, (Dec. 22, 2025), https://www.doi.gov/pressreleases/trump-administration-protects-us-national-security-pausing-offshore-wind-leases.

[32] Clare Fieseler, ‘Bonkers’ DOI Letter Halts All Five In-Progress Offshore Wind Farms, Canary Media (Dec. 22, 2025), https://www.canarymedia.com/articles/offshore-wind/bonkers-doi-letter-halts-all-five-in-progress-offshore-wind-farms.

[33] U.S. Dep’t of Transp., Trump’s Transportation Secretary Sean P. Duffy Terminates and Withdraws $679 Million in Funding for Offshore Wind Projects at Ports (Aug. 29, 2025), https://www.transportation.gov/briefing-room/trumps-transportation-secretary-sean-p-duffy-terminates-and-withdraws-679-million.

[34] Id.

[35] Solar Energy Indus. Ass’n, American Energy Under Threat: Political Attacks Threaten Half of All Planned Power in the U.S. (Nov. 2025).

[36] Id.

[37] Id.

[38] Id.

[39] N. Am. Elec. Reliability Corp., 2025 Summer Reliability Assessment 18 (May 2025).

[40] Id. at 19.

[41] Exec. Order No. 14261, Reinvigorating America’s Beautiful Clean Coal Industry, 90 C.F.R 15517 (2025), https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2025-04-14/pdf/2025-06380.pdf.

[42] U.S. Dep’t of Energy, Energy Secretary Issues Emergency Order to Secure Grid Reliability Ahead of Summer Months (May 23, 2025), https://www.energy.gov/articles/energy-secretary-issues-emergency-order-secure-grid-reliability-ahead-summer-months.

[43] Exec. Order No. 14261, Reinvigorating America’s Beautiful Clean Coal Industry, 90 C.F.R 15517 (2025), https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2025-04-14/pdf/2025-06380.pdf.

[44] Marianne Lavelle, Trump’s Order to Keep Michigan Coal Plant Running Has Cost $80 Million So Far, Inside Climate News, (Oct. 31, 2025), https://insideclimatenews.org/news/31102025/michigan-campbell-coal-plant-operation-has-cost-80-million/.

[45] Michael Goggin, The Cost of Federal Mandates to Retain Fossil-Burning Power Plants, 7, Grid Strategies LLC, On Behalf of Earthjustice, Environmental Defense Fund, Natural Resource Defense Council and Sierra Club (2025).

[46] US postpones Wyoming coal lease sale after disappointing Montana auction, Reuters, Oct. 9, 2025, https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/us-postpones-wyoming-coal-lease-sale-after-disappointing-montana-auction-2025-10-08/.

[47] Grid Strategies LLC, National Load Growth Report: 2024 Edition (2024).

[48] Diana DiGangi, Gas turbine manufacturers expand capacity, but order backlog could prove stubborn, Utility Dive, (Sept. 5, 2025), https://www.utilitydive.com/news/mitsubishi-gas-turbine-manufacturing-capacity-expansion-supply-demand/759371/.

[49] Lazard, Levelized Cost of Energy Analysis – Version 18.0 (2025).

[50] Lazard, Levelized Cost of Energy Analysis – Version 18.0 (2025).

[51] Jeff St. John, Forcing Dirty Power Plants to Stay Open Would Cost Americans Billions, Canary Media (Aug. 14, 2025), https://www.canarymedia.com/articles/policy-regulation/forcing-dirty-power-plants-to-stay-open-would-cost-americans-billions.

[52] The European Union pursues carbon neutrality with policy consistency that attracts long-term investment. See European Commission, The European Green Deal, COM(2019) 640 final (Dec. 11, 2019), https://ec.europa.eu/info/strategy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal_en. India, Middle Eastern nations, and Southeast Asian countries increasingly view renewables as paths to energy access and economic development. See International Energy Agency, India Energy Outlook 2024 87 (2024); Joseph S. Nye et al., The New Geopolitics of Energy, Ctr. for Strategic & Int’l Studies 45 (2024).

[53] International Energy Agency, World Energy Investment 2024 45-48 (2024), https://www.iea.org/reports/world-energy-investment-2024.

[54] Inflation Reduction Act, Pub. L. No. 117–169, 136 Stat. 1818 (2022).

[55] Wood Mackenzie, US Clean Energy Manufacturing Post-OBBB (Sept. 15, 2025). See also, Clean Investment Monitor: Q2 2025 Update, Rhodium Group (August 28, 2025), https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/64e31ae6c5fd44b10ff405a7/68b07af49e0e4b1538c493d6_Clean%20Investment%20Monitor%20Q2%202025%20Update.pdf.

[56] Lazard, Levelized Cost of Energy Analysis – Version 17.0 9-12 (2024); International Energy Agency, World Energy Outlook 2024 112 (2024).

[57] Galen Barbose et al., Lawrence Berkeley Nat’l Lab., Retail Electricity Rates, Bills, and Price Trends: 2024 Edition (Oct. 2025).

[58] Id. at 42–48.

[59] Ryan Wiser et al., Renewable Energy and Retail Electricity Prices, Lawrence Berkeley Natl. Lab., LBNL-2001432, at 18 (2024).

[60] U.S. Energy Info. Admin., State Energy Data System (SEDS): 2024 (2024), https://www.eia.gov/state/seds/.

[61] Id.

[62] Press Release, Americans for a Clean Energy Grid, New Report Reveals U.S. Transmission Buildout Lagging Far Behind National Needs (Updated July 23, 2025), https://www.cleanenergygrid.org/new-report-reveals-u-s-transmission-buildout-lagging-far-behind-national-needs/.

[63] Princeton Univ. ZERO Lab, Net-Zero America: Potential Pathways, Infrastructure, and Impacts 87 (2023); Edison Elec. Inst., Transmission Investment Report 2024 15 (2024).

[64] Building for the Future Through Electric Regional Transmission Planning and Cost Allocation and Generator Interconnection, Order No. 1920, 187 FERC ¶ 61,068 (2024), order on reh’g, Order No. 1920-A, 189 FERC ¶ 61,049 (2024), order on reh’g, Order No. 1920-B FERC ¶ 61,043 (2025).

[65] Id.

[66] Id.

[67] Id.

[68] Joseph Rand et al., Queued Up: Characteristics of Power Plants Seeking Transmission Interconnection as of the End of 2023, Lawrence Berkeley Natl. Lab., LBNL-2001540, at 8-12 (2024).

[69] Improvements to Generator Interconnection Procedures and Agreements, Order No. 2023, 184 FERC ¶ 61,054 (2023).

[70] Letter from Chris Wright, Sec’y of Energy, to David Rosner, Chairman, FERC, Re: Secretary of Energy’s Direction that the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission Initiate Rulemaking Procedures and Proposal Regarding the Interconnection of Large Loads Pursuant to the Secretary’s Authority Under Section 403 of the Department of Energy Organization Act (Oct. 23, 2025), https://www.energy.gov/sites/default/files/2025-10/403%20Large%20Loads%20Letter.pdf.

[71] Notice of Proposed Rulemaking, Large Load Interconnection, FERC Docket No. RM25-4-000 (issued Jan. 16, 2025); see also Emma Penrod, Large load tariffs could streamline interconnection by shrinking queues: Enverus, Utility Dive, (Dec. 18, 2025), https://www.utilitydive.com/news/large-load-tariffs-could-streamline-interconnection-by-shrinking-queues-en/808190/.

[72] H.R.4776 – 119th Congress (2025-2026): SPEED Act, H.R.4776, 119th Cong. (2025). See also Seven County Infrastructure Coalition v. Bureau of Land Management, 145 S. Ct. 1497 (2025).

[73] H.R.4776 – 119th Congress (2025-2026): SPEED Act, H.R.4776, 119th Cong. (2025).

[74] Ethan Howland, Why the SPEED Act may slow down after passing the House, Utility Dive, (Dec. 22, 2025), https://www.utilitydive.com/news/senate-permitting-reform-speed-act/808471/.