Agriculture, Animals, and AI – Modern Solutions for Age-Old Problems

by Scott Scribi

When you think of Artificial Intelligence (“AI”), folks usually point towards ChatGPT, not agriculture. However, this modern technology extends to help farmers effectively and sustainably pursue their practice. Whether it is ensuring the health of their crops, monitoring livestock, harvesting, or conserving energy, AI has advanced the productivity and in turn the environmental impact of agriculture. One thing is for certain, AI plays a large role in the agricultural field, and will only get larger in the future.

AI’s Impact on Agricultural Sustainability

AI is a breakthrough in the agricultural field, not just for the efficiency that it brings to farmers, but also for the environmental benefits it can provide. AI supports sustainable agriculture which aims to produce quality products that protect the environment and also protect and aid farm animals. Technologies like Nofence help farmers keep track of their livestock, recognize their behaviors, and optimize their well-being and safety. This technology enables a grazing-based dairy system, which studies have shown provides an energy usage reduction of 35%. Smaxtec has developed TruAdvice, which monitors and alerts diseases in cows, enabling farmers to respond quicker and more directly. Other high-tech tools help reduce fertilizer use by observing and analyzing soil, which helps minimize runoff pollution into waterways. Even cannabis companies utilize AI technology; Growlinkprovides constant oversight into the production and health of each plant and implements changes to best suit their growth.

Each of these budding technologies aims to optimize the time and value of its customers, but also provides long-term health and stability benefits to the environment. Additionally, these systems are more effective the more integrated they become. Each farmer that provides information to the technology strengthens the reliability and function of the product. Machine learning algorithmspredict outcomes, assign probabilities, and update understanding from the results. Put simply, the more frequently AI is used, the more effective it becomes.

Growing AI Use in the Agricultural Field

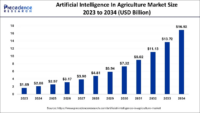

Perhaps nothing is more persuasive for the effectiveness of AI than its rapid growth in the agricultural field. In 2017, the investment value for AI technologies totaled nearly 520 million dollars; it is expected to be 2.6 billion by 2025. But it isn’t projected to slow down – rather, it will speed up. Research suggests that artificial intelligence investment will reach almost 17 billion in ten years.

Perhaps equally as important is the availability of these technologies to not just large-scale producers, but smaller, local businesses. Indeed, smallholder farmers grow nearly 70% of the world’s food, each owning land less than two and a half acres. The Northeast Dairy Business Innovation Center, a multi-state initiative program, offered grants totaling $45 million to smaller farms throughout New England for AI technology. Having AI technology accessible to smaller businesses serves to enhance the technology by exposing it to additional data points to enable more of the industry to understand and implement AI.

This technology is not just limited to the United States. Crop Protection AI is one of the various technologies being implemented in Africa. It is a low-cost tool that is easy to understand and utilize. Through machine learning, Crop Protection AI prevents unnecessary pesticide use, reduces pesticide pollution, and analyzes deficiencies in crops. Since farmers in Africa lose about half of their crops to pests each year, this AI technology would provide significant economic benefits to farmers and improve their productivity.

The Benefits AI Provides to the Environment Offsets its Energy Exertion

It is undisputed that AI technology has the potential to significantly sap electricity consumption and exert unprecedented levels of energy. Indeed, data centers in 2022 made up 2% of electricity demand across the globe. AI technology is projected to double its consumption by 2026. Nearly 30% of the world’s energy consumption is from agricultural ventures.

However, it is important to note that the energy drain from AI depends on the form of its usage. For example, AI tasks that generate images exhaust an enormous amount of energy, thousands of times more than non-generative tasks. Since the AI models utilized by farmers are only for a specific purpose, its energy usage is only a fraction of what generative systems, like ChatGPT, consume.

Additionally, AI tools in the agricultural field create a positive impact on the environment by ensuring sustainability. Targeted irrigation and fertilization methods help minimize the environmental footprint of farming. AI technology mitigates soil erosion and greenhouse gas emissions. Overall, researchers estimate that AI can reduce energy consumption up to 15%.

It also has even better results for indoor agriculture. Researchers found that AI systems can reduce energy consumption for indoor farms by up to 25%. By managing sophisticated lighting and climate regulation systems to be as efficient as possible, it cuts at the carbon footprint and makes indoor farms more sustainable and viable.

Finally, AI is making impacts on sustainable energy generation. Machine learning algorithms maximize the ability for renewable energy systems like wind turbines and solar panels. The link between sustainable energy and agriculture has only become strongerwith time. Thus, AI can serve to both aid farmers in sustainable, effective cultivation and create more clean, sustainable energy.

Conclusion

AI technology is here to stay and has positive implications for the agricultural field. As AI continues to grow, it can bring more efficient, more sustainable systems to farmers. This technology not only minimizes energy output but even conserves energy in its processes. With local farms having access to AI, it will expand its accessibility and efficiency, creating more sustainable systems and ensuring effective tools for farmers to rely on.