Cruelty for Me but Not for Thee: How Vermont’s Animal Cruelty Laws Could Protect Farmed Animals

By Anthony Corradi

Complaints of animal cruelty in Vermont rarely result in a change to an animal’s status. Voluntary compliance or enforcement via civil or criminal penalties only occur in 21% and 1.3% of cases respectively.[1] There are many reasons for this, including the fragmentation of the law’s enforcement and lack of knowledge as to what constitutes a violation.[2] Cases involving livestock and poultry are even rarer given the deference afforded to accredited animal husbandry practices.[3] Despite these challenges, an analysis of Vermont’s animal cruelty statute shows that Vermont can—and should—enforce a provision of the law to inhibit several common methods of farmed animal confinement.

The Vermont Legislature wrote the animal cruelty statute with the broad purpose of “prevent[ing] cruelty to animals.”[4] Correspondingly, the State should interpret and enforce the law to respect its breadth.[5] The statute states that one commits criminal cruelty when one “[t]ies, tethers, or restrains . . . livestock, in a manner that is inhumane or is detrimental to its welfare.”[6] This provision further exempts “[l]ivestock and poultry husbandry practices.”[7] However, in defining this term, the legislature did not simply defer to common or accepted industry practices. Instead, a three-part conjunctive test requires, in part, that farmers raise animals consistent with “husbandry practices that minimize pain and suffering.”[8] This language creates a powerful exception (to the exception) for farmed animals.

The State need not prove that farmers tying or restraining animals intended to act in a manner detrimental to the animal’s welfare. In State v. Gadreault, the Vermont Supreme Court held that this provision creates a strict liability offense.[9] Thus, Vermont only needs to show that a farmer has voluntarily tied or restrained an animal in a manner that causes harm.[10]

Further, because husbandry practices must minimize pain and suffering to be exempt from the cruelty statute imposes a real limit on acceptable farming techniques.[11] Since the legislature did not define “minimize,” we start with the dictionary definition.[12] The dictionary defines “minimize” as: “to reduce or keep to a minimum,”[13] where “minimum” means “the least quantity . . . possible.”[14] While some may interpret these definitions as only requiring a nominal reduction in pain and suffering, a straight reading requires farmers to take non-cost prohibitive measures to eliminate pain and suffering at any cost. The Vermont Supreme Court has not resolved this ambiguity in the context of the animal cruelty statute, as it has done in other statutes.[15] In those cases, the Court has generally taken the middle route, holding that one meets a mandate to “minimize” when a fact-intensive inquiry shows evidence of reasonable and concrete steps taken to mitigate negative effects.[16]

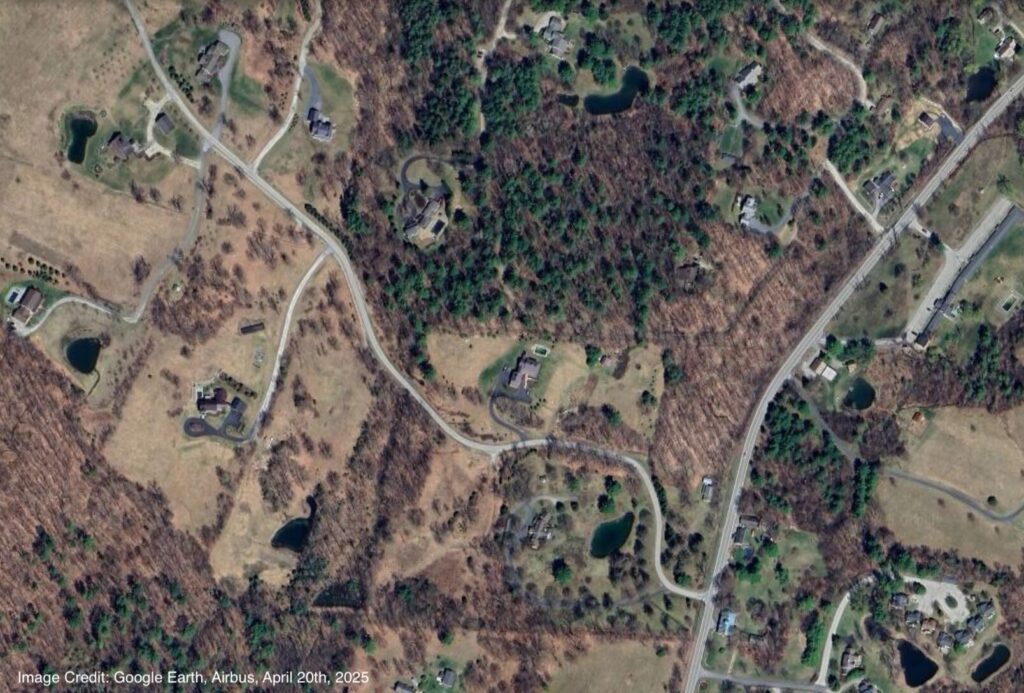

Accordingly, Vermont could use its current animal cruelty law to prevent several types of on-farm confinement such as battery cages and veal crates. Of special relevance to dairy-loving Vermont, though, is the “tie stall.” Tie stalls are a housing scheme in which farmers confine a cow to a narrow stall by a neck collar and chain.[17] Numbers for Vermont alone are unavailable, but as of 2014 between 20% and 42% of cows were kept in tie stalls in the eastern U.S.[18] These are likely conservative estimates for Vermont as the data also showed tie stall usage increased as herd size decreased.[19]

In a potential criminal or civil enforcement action, the State would need to show that confining a cow in a tie stall is a voluntary act done in a manner that is detrimental to the cow’s welfare. Of course, farmers choose to use tie stalls, and thus the voluntary requirement would generally be irrelevant. The question of the cow’s welfare is only slightly more difficult. Farmers can point to certain benefits of tie stall use that are incidental to a lack of outdoor freedom—such as the reduced prevalence of foot lesions.[20] Conversely, the negative effects of tie stalls are more numerous and arguably more severe. Harmful outcomes include disrupted natural lying behaviors, increased physiological stress levels and injury rates, and decreased emotional states.[21] As farmers and governments alike have concluded from similar observations and data, tie stalls are almost certainly more detrimental to cows’ welfare than not.[22]

Harmful or not, however, tie stalls are an accredited animal husbandry convention. Thus, Vermont would still need to show that the customary livestock practice exception should not apply. Here, the exception is void if the farmers using tie stalls have not taken reasonable actions to mitigate cows’ pain and suffering. Considering the statute’s broad purpose, the State could likely show that any act short of replacing tie stalls with free housing is unreasonable. Even if not, farmers would have to submit evidence of concrete steps taken to reduce the harm of tie stalls. Though less desirable than an outright exclusion, this would still reduce extended or permanent tie stall use as outdoor access is the clearest way to reduce negative outcomes.[23]

The State’s inaction on farmed animal cruelty is not solely due to a lack of legal authority. To the contrary, the Vermont Legislature and Supreme Court has made it clear that the law applies to farmers who do not take reasonable steps to reduce harm. This surely implicates the use of objectively detrimental practices like tie stalls, veal crates, or battery cages without further mitigating action. As a result, Vermont’s prosecutors and courts have a powerful tool—should they choose to utilize it—that could improve the lives of vast numbers of animals.

[1] Vt. Animal Cruelty Task Force, Report to Vermont House and Senate Judiciary Committees 23 (2016), https://legislature.vermont.gov/assets/Legislative-Reports/ACTF-Report-to-Judiciary-2016-FINAL.pdf.

[2] Id. at 22–24.

[3] Id. at 23.

[4] Vt. Stat. Ann. tit. 13, § 351a (2024).

[5] See In re SM Farms Shop, LLC, 2025 VT 33, ¶ 10 (“[O]ur primary goal is to give effect to the legislative intent.”).

[6] Tit. 13, § 352(3).

[7] Id.

[8] Id. § 351(13)(C) (emphasis added).

[9] 171 Vt. 534, 536 (2000) (concluding strict liability offense since punishment not severe and provision lacking intent element other provisions include).

[10] Id. at 537, (holding that “the restraint need only be detrimental” and “the perpetrator’s actions be voluntary”).

[11] See In re SM Farms Shop, LLC, 2025 VT 33, ¶ 10 (“[W]e presume that language is inserted advisedly and that the Legislature did not intend to create surplusage.”).

[12] See Id. ¶ 31.

[13] Minimize, Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/minimize (last visited Oct. 21, 2025).

[14] Minimum, Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/minimum (last visited Oct. 21, 2025).

[15] See e.g. In re Appeal of Shaw, 2008 VT 29 (analyzing whether tower’s visibility “minimized” as required by zoning ordinance).

[16] Id. ¶ 14–17.

[17] U.S. Dep’t of Agric., Dairy Cattle Management Practices in the United States, 2014, at 4 (2016), https://www.aphis.usda.gov/sites/default/files/dairy14_dr_parti_1.pdf.

[18] Id. at 160, 165 (20% of non-lactating “dry” cows and 42% of lactating “wet” cows).

[19] Id. at 159, 163.

[20] Annabelle Beaver et al., The Welfare of Dairy Cattle Housed in Tiestalls Compared to Less-Restrictive Housing Types: A Systematic Review, 104 J. Dairy Sci. 9383, 9406 (2021), https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0022030221007177?ref=cra_js_challenge&fr=RR-1.

[21] Id. at 9401, 9406.

[22] Emily Fread, Transitioning From a Tie Stall to a Freestall, PennState Extension, https://extension.psu.edu/transitioning-from-a-tie-stall-to-a-freestall (last updated Aug. 15, 2024).

[23] Beaver, supra note 20, at 9392.