Can You Dig It? Artificial Pond Construction in Vermont

By Dane Whitman

“What I have observed of the pond is no less true in ethics. It is the law of average.”[1]

In 1901, the Harvard Law Review published an article stating, “[a]lthough comparatively little has as yet been written about the law of ponds, the decisions are hopelessly confused.”[2] One could argue that, since then, ponds continue to attract relatively little attention in the field of environmental law. Rather than perform an extensive review of the “law of ponds” (previously attempted by Samuel Warren and Louis Brandeis in the 1889 edition of Harvard Law Review),[3] this blog post will explore a narrower topic: artificial pond construction in Vermont.

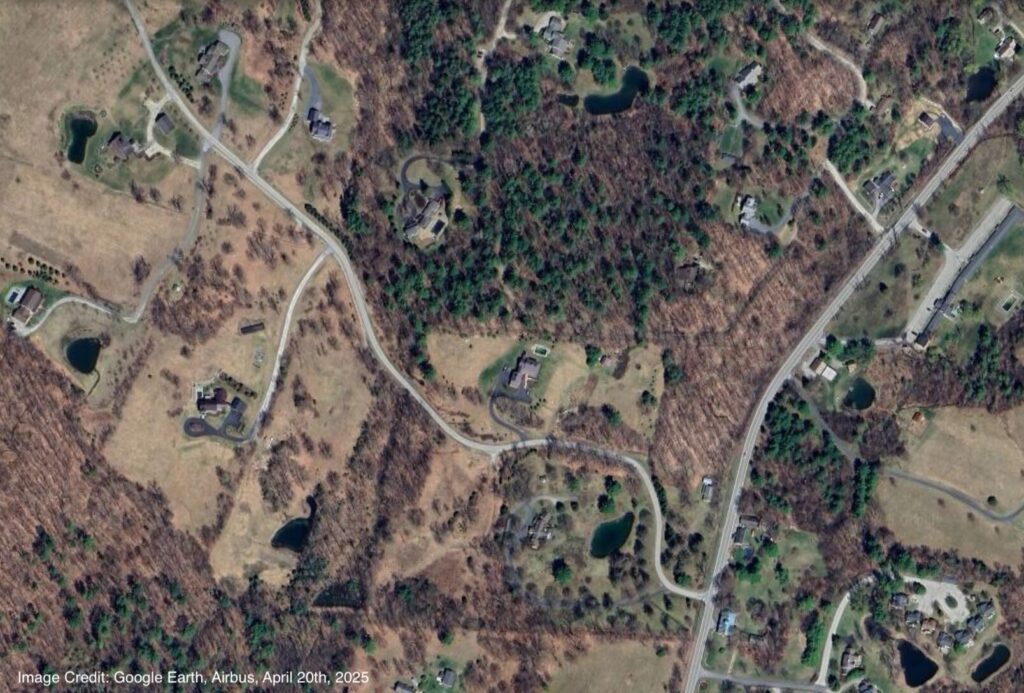

Vermont is home to “hundreds of small ponds, many of which provide a great habitat for plants, animals, and people.”[4] Satellite images over Vermont (such as the title image) reveal a landscape sprinkled with countless kidney-bean-shaped pockets of water seemingly unconnected to natural waterways.[5] Are these pools the result of lawless backwoods excavations? Or are backyard ponds evidence of Vermonters exercising their property rights to improve the local ecosystem? An overview of Vermont’s legal landscape suggests that there are both environmental opportunities and considerable risks regarding artificial ponds.

One example of a Vermont homestead utilizing artificial ponds for environmental benefits is Whole Systems Research Farm in the Mad River Valley.[6] The farm’s owner, Ben Falk, excavated a pond that catches rainwater and snowmelt from the upper portions of the property and then irrigates a series of terraced rice paddies.[7] The pond serves as a “bathroom” for his domestic ducks, and therefore the pond water irrigating the rice paddies is “rich in nutrients.”[8] The two small paddies are scaled for subsistence farming, producing enough rice “to satisfy the grain needs of a family of four.”[9]

Amy Siedl, a biologist and lecturer at the University of Vermont, has cited Falk’s farm as a model for climate adaptation.[10] Seidl has suggested that, given the Northeast’s increasing precipitation from climate change, artificial pond systems such as Falk’s are well-suited to capture rain from these events.[11] For example, Falk’s rice crop “thrives” during historic rain events, such as Hurricane Irene, whereas many of Vermont’s corn farmers have struggled with increasingly wet soil conditions.[12]

The remarkable potential of these artificial ponds begs the question: are they legal? Most prudent property owners might be intimidated by the prospect of renting an excavator and breaking ground without performing due diligence. Fortunately, Vermont regulators provide guidance (often accompanied by disclaimers of liability) for property owners to dig ponds that are structurally safe and environmentally sound.

To some extent, Vermont law supports property owners to construct artificial ponds. For example, Vermont’s statutes expressly allow property owners to stock and harvest fish from “artificial ponds.”[13] This requires, however, that “the sources of water supply for such pond are entirely upon his or her premises or that fish do not have access to such pond from waters not under his or her control . . . .”[14] In essence, this statute facilitates backyard fish farming, also known as “aquaculture.”[15]

Vermont’s administrative agencies also provide ample guidance for property owners who wish to excavate and manage artificial ponds on their property. Some of this guidance is practical, ranging from siting considerations; water supply needs; various depth requirements for fish versus waterfowl; which kinds of ponds require engineering consultation; and even a directory of excavation contractors.[16] The State also points potential pond owners to information regarding the best fish to stock, a list of native plants to prevent erosion, methods to maintain water quality for swimming, and how to optimize bird watching potential.[17]

While state resources appear to enable (if not encourage) pond construction, these materials also carry a strong dose of caution. Any pond “capable of impounding more than 500,000 cubic feet of water” will essentially constitute a dam requiring approval by the Department of Environmental Conservation.[18] For some perspective, a person could cover an acre of land with an 11-foot deep pond and still be shy of 500,000 cubic feet of water.[19] The Department explains, however, that even dams for small backyard ponds “are significant structures that can have major public safety and environmental implications.”[20] A variety of local, state, and federal laws can affect dam ownership, and more information can be found on Vermont’s Dam Safety Program website.[21]

Based on the specifics of a project, a suite of other regulatory entitles may also have a stake in your pond construction. Any construction that impacts a stream may require a stream alteration permit with Vermont’s River Management Program.[22] Any pond work that comes within fifty feet of a wetland may require a permit through Vermont’s Wetlands Program.[23] Other considerations include rare, threatened, and endangered species; fish and wildlife; local zoning bylaws; Vermont’s Act 250; historic or archaeological significance; and Vermont’s water quality standards.[24]

Of course, a great variety of tort and property law claims could also involve a pond. One illustrative case dates back to 1909, when a plaintiff successfully argued that mosquitos breeding behind a newly constructed dam caused him and his family to contract malaria.[25] While this was a Georgia case, the court’s words of wisdom apply to any Vermonter hoping to stay a good neighbor while constructing a new pond:

[I]n the construction of dams and in the backing of water they must choose their sites with due regard to the surroundings. They are not authorized to maintain stagnant ponds, polluted pools of water, or places in which mosquitoes breed, in unusual numbers to the endangering of the health of surrounding communities.[26]

Artificial ponds may provide an immediate opportunity for Vermont’s property owners to enhance biodiversity, climate resiliency, and land productivity on a hyper-local scale. Property owners should, however, perform due diligence to mitigate any potential environmental, public health, or safety issues associated with pond construction and maintenance. Nonetheless, it may be well worth the effort to hear choruses of frogs singing through the night; to watch birds inspecting the shoreline; or to ponder over schools of fish—all thriving because somebody dug a hole in the right place.

[1] Henry David Thoreau, Walden 188 (1854).

[2] Note, Rights in Public Ponds, 15 Harv. L. Rev. 68, 68 (1901).

[3] See generally Samuel D. Warren & Louis D. Brandeis, The Law of Ponds, 3 Harv. L. Rev. 1 (1889).

[4] Private Ponds, Agency of Nat. Res. Dep’t. of Env’t. Conservation, https://dec.vermont.gov/watershed/lakes-ponds/private-ponds (last visited Sept. 17, 2025).

[5] Image Credit: Google Earth, Airbus, (Apr. 20, 2025).

[6] Whole Systems Research Farm, Whole Systems Design, https://www.wholesystemsdesign.com/project-wsd-research-farm (last visited Sept. 17, 2025).

[7] Adam Regn Arvidson, Post-oil Groceries, 101 Landscape Architecture Mag. 54, 54 (2011).

[8] Id.

[9] Id.

[10] Audrey Clark, Facing Climate Change: Collapse or adaptation? Biologist Says Humans Can Adjust to Warmer World, vtdigger, (June 30, 2013), https://vtdigger.org/2013/06/30/facing-climate-change-collapse-or-adaptation-biologist-says-humans-can-adjust-to-warmer-world/.

[11] Id.

[12] Id.

[13] 10 V.S.A. § 5210.

[14] Id.

[15] George Devault, Small Scale Backyard Fish Farming, MOTHER EARTH NEWS, (Dec. 30, 2023), https://www.motherearthnews.com/homesteading-and-livestock/backyard-fish-farming-zmaz06amzwar/.

[16] Agency of Nat. Res. Dep’t of Env’t Conservation Water Quality Div., Vermont Pond Construction Guidelines (2006), https://anrweb.vt.gov/PubDocs/DEC/WSMD/Lakes/Docs/lp_pond-construction.pdf.

[17] Private Ponds – Pond Construction, Agency of Nat. Res. Dep’t of Env’t Conservation, https://dec.vermont.gov/watershed/lakes-ponds/private-ponds/private-ponds-pond-construction (last visited Sept. 17, 2025).

[18] 10 V.S.A. § 5210.

[19] Agency of Nat. Res., supra note 17.

[20] Private Ponds: What You Should Know About Constructing a Pond Or Dam, Agency of Nat. Res. Dep’t of Env’t. Conservation https://dec.vermont.gov/sites/dec/files/wsm/lakes/Ponds/Constructing%20a%20Private%20Pond%20Update.pdf (last visited Sept. 17, 2025).

[21] Id.

[22] Id.

[23] Id.

[24] Id.

[25] Towaliga Power Co. v. Sims, 65 S.E. 844, 845 (Ga. Ct. App. 1909).

[26] Id.