VJEL Staff Editor: Brad Farrell

Faculty Member: Rachel Stevens

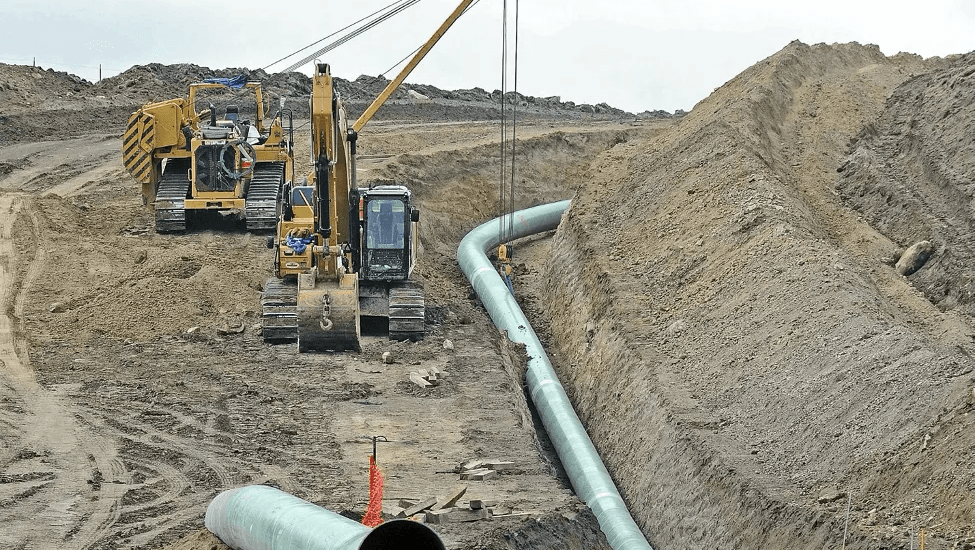

Unearthing Virtual Pipelines

The oil and gas pipeline network in the United States stretches nearly three million miles, with another 21,500 miles currently proposed or under construction. Since July 2020, however, frontline communities and environmental advocates successfully challenged the most significant of these proposed pipelines: Keystone XL, Dakota Access, and Atlantic Coast. The 2,600-mile Keystone XL pipeline hit a major roadblock when the Supreme Court upheld an orderissued by a Montana federal court to stay the pipeline. Simultaneously, Dominion Energy announced the cancellation of the Atlantic Coast pipeline project and the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia ordered the Dakota Access pipeline to shut down pending further environmental review, handing down a victory to the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe and other groups opposing the pipeline. Meanwhile, the significant reduction in travel due to COVID-19 has sunk oil demand and prices and led to a glut of petroleum as oil and gas companies opt to keep their products moving rather than decrease production.

Confronting these legal battles and shifting economics, oil and gas companies are rapidly moving their products above ground, turning to trucks, trains, and tankersknown as “virtual pipelines“to transport and store oil and gas on roads, rails, and waterways. Since the pandemic began, California residents witnessed dozens of oil tankers idling just offshore from the Port of Los Angeles being used for floating storage of 20 million barrels of oil. Gulf Coast residents confronted a flotilla of nearly 20 tankers, including very large crude carriers, floating offshore from Saudia Arabia waiting to unload in U.S. ports. Inquiries from oil and gas companies for available truck and train transport has also intensified since the pandemic.

Undoubtedly, environmentalists have had success making pipeline challenges the frontline in the fight against fossil fuels and climate change. But these legal victories are short lived if oil and gas companies revert to virtual pipelines which last made significant national headlines in 2014, before the Dakota Access pipeline was in service and before President Obama rejected the Keystone XL pipeline. The Association of American Railroads estimates that carloads of crude oil on U.S. railroads peaked in 2014 at 493,146, falling sharply the next few years as the Trump Administration fast tracked traditional pipelines.

This shift to virtual pipelines is moving forward without public scrutiny or environmental review, even though the associated safety and environmental risks may be more detrimental than traditional pipelines. Shipping crude oil and gas via virtual pipelines may have greater environmental costs than traditional pipelines because trains and trucks emit ground level air emissions, burn diesel fuel, and have a greater risk of spilling in populated areas. One study of crude-oil-by-rail transported out of North Dakota estimates that the “air pollution and greenhouse gas costs are nearly twice as large for rail as for pipelines.”

Virtual pipelines also present well documented safety risks. Truck brakes and exhaust systems can heat to upwards of 1,000 degrees Fahrenheit, temperatures that would easily ignite leaking natural gas in the event of a leak or a crash. A truck driver in New York fell asleep at the wheel and careened down an embankment, leaking natural gas. In July of 2013, a major accident in Quebec killed 47 people. Another accident in Alabama started an inquiry into the lack of oversight on virtual shipping methods. This boom in train and truck oil transportation has directly correlated to increased spills. In 2013 alone, more gallons of oil spilled due to rail accidents than the previous total from 1975 to 2012.

These hazardous transportation methods are regulated by the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration (PHMSA) which issues special permits and writes specifications for these tank cars, as well as for all highway, railroad, and barge tanks carrying hazardous materials. Companies can receive special permits to transport compressed gas on the roadways by showing their canisters withstand front, rear, and side-impact as well as rollovers. This permitting process currently does not involve an environmental review under the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) that would otherwise require a “hard look” at the virtual pipeline’s environmental impacts. Gas transported in these PHMSA certified containers reaches more geographic areas than traditional pipelines could, expanding the demand and infrastructure related to natural gas without evaluating the environmental impact of the virtual pipeline.

The transportation of highly flammable substances by virtual pipeline may be entering a new boom now that the PHMSA promulgated a rule in August 2020 that allows railways to transport liquified natural gasleading some to worry about “bomb trains” rolling through neighborhoods. Virtual pipelines may also prolong the life of oil and gas by expanding into to new regions like New England, where the terrain will not support traditional pipeline development.

Looking ahead, a move to virtual pipelines may accelerate under the new Biden Administration as oil and gas companies seek new forms of transportation that avoid environmental review. Although president-elect Biden will seek to expand the renewable energy market in all 50 states, he campaigned on a promise that he will not ban fracking. If the Biden Administration opposes traditional pipelines, like the Obama Administration, then oil and gas companies will simply pivot to road and rail distributions. To mitigate this shift to virtual pipelines, federal and state governments must incentivize renewable energy to levels that upset the status quo and reverse the Trump Administration’s environmental rollbacks. Otherwise, oil and gas companies will continue building fossil fuel infrastructure through virtual pipelines that avoid environmental review and present serious risks to public health, safety, and the environment. The pipeline wars have made significant strides in the battle against fossil fuels by blocking what will hopefully be obsolete energy infrastructure, but without federal leadership and policies that incentivize renewable energy the benefits of those fights are not fully realized.