2022 TOP 10 BLOG

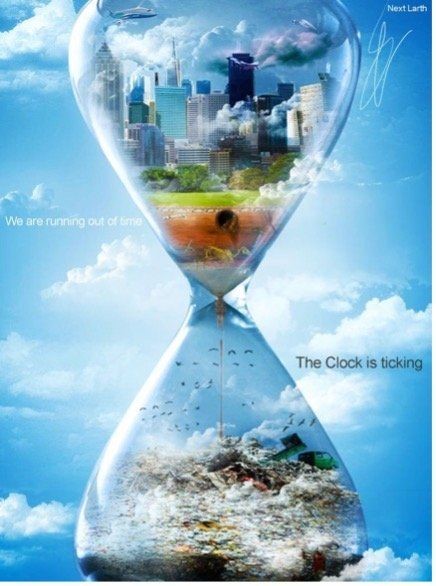

Running Dry: An Emptying Hourglass on Biden’s Climate Goals

VJEL Staff Editor: Adam Washburne

Faculty Member: Kevin Jones

Introduction

Four individual petitions for certiorari (cert) were consolidated and granted writ of cert on Friday, Oct. 29, 2021. Each of the four petitions were considered by the Supreme Court for several suspense-filled months leading up to the Court’s late October 2021 conference. These petitions challenge the EPA’s authority to regulate greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, especially CO2, from electricity-generating coal-fired power plants. Each petition was filed in response to D.C.’s Circuit Court decision in Am. Lung Ass’n v. EPA, 985 F.3d 914 (D.C. Cir. 2021). In the American Lung Association case the circuit court vacated the EPA’s Affordable Clean Energy (ACE) rule. In doing so, the court created a blank canvas for the Biden-era EPA to draft a new emissions reduction rule. As of November 29, 2021 Michael Regan, the new EPA administrator, has yet to release any such new rule. Regardless, arguments are expected to begin in Summer, 2022.

The extent of the EPA’s authority and responsibility to regulate GHGs has been challenged since the agency’s inception in 1970. But after the Supreme Court’s decision in Massachusetts v. EPA (2007) the agency has had judicial precedent from the highest Court supporting the agency’s authority and mandating the agency’s responsibilities in regulating GHG emissions (including but not limited to CO2). In American Lung Association, the D.C. Circuit Court upheld the Massachusetts precedent. However, this case now finds itself in front of a more conservative-leaning Supreme Court. Therefore, as we head into this litigation, the looming question for the future landscape of environmental law is how the current Supreme Court will rule, regarding the authority and responsibilities of the EPA in regulating emissions from stationary sources (especially existing coal-fired electric generating power plants) going forward.

American Lung Association v. EPA vacated the Trump-era ACE rule and appeared to give the Biden-era EPA a blank canvas to draft a new emissions reduction rule

Under conservative presidential administrations the EPA has traditionally sought to shrink the scope of its authority and mandate. Conservative EPA administrators have traditionally asserted what the agency cannot do. In October 2020, conservative EPA administrator Andrew Wheeler took the same position in American Lung Association v. EPA. Wheeler’s EPA defended the self-imposed limitations within the Trump-era Affordable Clean Energy (ACE) rule. This 2019 rule effectively repealed the Obama-era EPA’s 2015 Clean Power Plan (CPP). The EPA’s 2019 ACE rule asserted that the agency’s ability to regulate CO2 emissions from electricity-generating coal-fired power plants was limited to strictly on-site emissions reduction solutions. The conservative EPA deemed that these “fence-line” reduction solutions or heat-rate improvements (technological upgrades/enhancements to older coal-fired power plants) were the best system of emissions reduction (BSER).

Wheeler’s EPA argued that the language of 42 U.S.C.S § 7411 (“Section 111”), within the Clean Air Act did not grant the agency authority to regulate GHG emissions through off-site or generation shifting emissions reduction solutions. Off-site solutions were the hallmark of the 2015 Obama-era CPP. Through both on-site and off-site solutions the CPP aimed to shift the production of electricity toward the energy sources with the lowest emissions and away from sources with the highest emissions (chiefly coal-fired power plants). By enforcing generation shifting the 2015 CPP sought to prioritize cleaner energy sources and deprioritize dirty energy sources.

The D.C. Circuit Court held in favor or vacating the 2019 ACE rule. The circuit court ruled that the underlying EPA interpretation of the statutory language of Section 111 did not include any on-site specific caveats to the EPA’s ability to determine the BSER. The circuit court asserted that Section 111 demanded that the EPA determine the BSER without such fence-line limitations. The court clarified that the statute’s BSER test included: “the cost of achieving such reduction and any non-air quality health and environmental impact and energy requirements.” The circuit court reasoned that this language required the EPA to consider more than merely on-site solutions suggested in the ACE rule.

With no new rule in place, the EPA again faces litigation. As a result, the petitions for cert that have been granted seem to be targeted at the language from the CPP and the general authority of the EPA as delegated from Congress. This is an unprecedented Supreme Court case dynamic where the Court has no Biden-era EPA rule or regulation to interpret.

The Supreme Court will consider four questions presented from a combination of conservative states and coal companies

There are four separate petitions that the Supreme Court consolidated into one case. Each petition, accepted by the Court, telegraphs some of the substance that we can expect to see within the arguments of the petitioners’ brief. This Supreme Court case will be referred to as West Virginia v. EPA (West Virginia first to file petition for cert after the American Lung Association decision). Let’s look at each of the four petitions chronologically, as they were filed with the Court.

I. West Virginia

This petition begins by subtly attacking the statutory authority granted to the EPA, referring to empowering-statute Section 111(d) as an “ancillary provision” of the Clean Air Act. This petition challenges whether Congress acted “constitutionally” when it gave the agency authority to issue “significant rules.” This petition challenges the EPA’s authority to “unilaterally decarbonize[e] virtually any sector of the economy.” This petition characterizes the EPA’s regulatory authority as too broad and far-reaching. This petition telegraphs West Virginia’s anticipated argument by using language of “constitutional” authority.

Petitioners appear to be preparing for a non-delegation doctrine argument. This kind of argument would challenge Congress’s ability to delegate its legislative powers to the EPA as an executive agency. This is a very large scale and difficult argument to mount. If petitioners lodge this argument they can expect push-back from the Supreme Court, since the non-delegation doctrine was expressly rejected by the Supreme Court in Whitman v. American Trucking Ass’n (2001) (challenging the EPA’s authority under the Clean Air Act). However, this does not mean that petitioners cannot present this argument with the hope of overturning this part of Whitman. It goes without saying that current Court makeup is more conservative than the Whitman Court. Ultimately, a non-delegation doctrine argument is a “can-of-worms” which would create far more new issues for the Court than it would potentially solve (beyond just the EPA).

II. North American Coal Corp.

The second petition challenges the extent of the agency’s power to determine the BSER. This petition challenges off-site solutions such as generation shifting by characterizing them broadly as “industry-wide systems such as cap-and-trade.” With this language the petitioners overarching challenge begins to take shape: agency overreach by the EPA. Unfortunately for petitioners, in attacking cap-and-trade schemes they are attacking previously successful programs that the EPA has implemented. Historically, the EPA has used cap-and-trade schemes to control GHGs with great success (see: cap and trade successfully reducing SO2 emissions to remediate acid rain).

Additionally, the off-site solutions that this petition targets seem to be from the Obama-era Clean Power Plan. The problem for petitioners here is that President Biden has publicly stated that his administration will not return to the Clean Power Plan. This portion of the petitioners’ argument appears to be “shadow boxing” with issues that are no longer or not yet relevant (especially not while the EPA has yet to draft a new emissions reduction plan).

III. North Dakota

The third petition challenges whether the EPA can “promulgate regulations for existing stationary sources that require states to apply binding nationwide ‘performance standards’ at a generation-sector-wide level.” This petition focuses on states’ authority in the determination and implementation of the EPA’s BSER. This argument challenges the EPA’s rule-making process, specifically as it relates to the role of the states in the process. Petitioners will likely argue that the EPA is operating unilaterally and outside of the scope of Section 111’s “cooperative-federalism” mandate. But the Clean Air Act clearly carves out space for states and private coal companies to pursue the specific means by which they implement the BSER set by the EPA. After seeing this petition, the EPA should be able to sidestep this argument altogether by simply incorporating language into their new rule, incorporating state input and assistance in determining and implementing the agency’s updated BSER.

The weakest part of this petition’s argument is almost too obvious: the EPA has not yet drafted a new rule to replace ACE (as of November 27, 2021). Until the EPA releases a rule, there is little-to-nothing in this question presented for the Court to decide. The Court could reemphasize the importance of cooperative federalism and provide guidance on what the EPA could not include in their new rule. But this kind of opinion would surely be equivalent to an advisory opinion, which we know the Court has had a long history of refusing to provide.

IV. Westmoreland Mining Holdings, LLC

The fourth and final petition in this consolidated case was granted only in part. The accepted portion uses the language of the major questions doctrine to challenge the EPA’s ability to regulate matters of “vast political and economic significance as whether and how to restructure the nation’s energy system.” The major question doctrine challenge was dealt with and settled already by the D.C. Circuit Court. The D.C. circuit ruled that regulating GHG emissions from power plants throughout the country falls “squarely within the EPA’s wheelhouse.” The court found that the EPA’s authority was supported both by Congress (in Section 111) and by the Court (in Mass. V. EPA).

Perhaps the most interesting thing about this particular petition is the rejected portion. The Supreme Court refused to grant cert for the question of whether 42 U.S.C.S. § 7412 (“Section 112”)—which already regulates emissions of coal-fired power plants for mercury gas emissions—would displace the EPA’s authority to regulate CO2 emissions from those same coal-fired plants. This partially omitted question may be positive sign. If the Court is not willing to consider the narrow issue of limiting the EPA’s Section 111 authority in light of current Section 112 regulations then it may take a more historically supported approach to interpreting the EPA’s Section 111 authority as challenged by some of the petitioners’ more cumbersome arguments.

Conclusion – A case without a rule to go on, the future of environmental protections

The most interesting thing about this upcoming case is that the Court granted cert at a time when the EPA does not have a stationary source emissions reduction rule in place. After the ACE rule was vacated by the D.C. Circuit Court’s decision, the Court is left with no rule to analyze. The Court could issue an opinion against a possible future rule. But this would be tantamount to building a “straw man” argument. This would be a dangerous and short-sighted precedent, even for this conservative Court.

The underlying theme of these consolidated petitions is agency overreach. Petitioners appear to be preparing to argue that off-site emissions reductions have too far reaching an effect on the overall energy industry and the economy for the EPA to be able to regulate beyond the fence-line. The language in these petitions should signal the EPA to prepare for a major questions doctrine and a non-delegation doctrine challenge to their authority. The roadmap to defend against these challenges is laid out by the court in American Lung Association’s case. In the past, the Court has upheld judicial precedent nullifying arguments based on these tenuous doctrines. But no matter how the EPA defends against these challenges, the big picture for the agency is its core mandate to protect our environment. The EPA should remind the Court that potential short-term economic reactions should be weighed properly against the imminent long-term health repercussions facing our planet and ourselves, without effective EPA regulations.