We Paved Paradise to Put Up with Parking Lots

Angie Kaufman

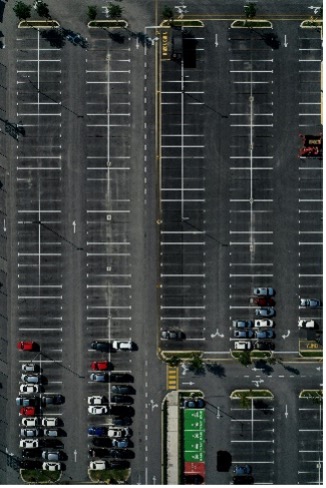

At first glance, the American parking lot may seem, well, boring; perhaps it’s helpful and convenient at best, benign at worst. However, the effects of parking reach far and wide as it drives urban sprawl, housing shortages, inequitable costs, and spatial injustice. Parking takes up nearly one third of the land in United States cities. This comes out to eight spaces per car, according to some estimates. In San Bernadino, California, parking takes up nearly fifty percent of the central city. Across the country, most land use practices prioritize scarce land and monetary capital for carsover housing. For example, parking spaces in Los Angeles take up more land than housing. As UCLA professor and parking policy specialist Donald Shoup stated, “Zoning requires a home for every car, but ignores homeless people.”

Traditionally, environmental justice refers to the disproportionate placement of industrial hazards in low-income communities and communities of color. But equal access to resources is also a foundational environmental justice principle. Car-centric zoning policies violate this principle by creating spatial injustice, the “[in]equitable allocation of socially valued resources,” like “jobs, political power, social services, environmental goods in space, and the [un]equal opportunities to utilize these resources over time.” A society designed for cars leads the way for sprawl and decentralized resources accessible only by car. Mandated amounts of parking, criminalization of pedestrians, and restrictive zoning laws have silenced urban centers and stripped them of vibrancy and resources. Car-dependence and urban sprawl limit people’s access to necessities like affordable housing and food security while exposing communities to more intense effects of climate change. Thoughtfully reshaping the law to encourage human-scale spaces that prioritize public transit and walkability can ameliorate spatial injustice by improving access to resources, affordable housing, food security, and opportunities in urban communities.

Historically, cars were seen as a status symbol. They were used primarily for sporting and entertainment, so long as you could afford the high cost of purchase and maintenance. Once manufacturers began mass producing cars, American car ownership soared. Today, high costs of purchase and maintenance remain with one crucial difference: cars are no longer a sporting luxury but rather a necessity in the daily lives of many Americans.

Through laws mandating parking minimums and zoning restrictions, corporate lobbying and market forces transformed much of the landscape from an approachable, human-scale model to one designed for cars. For example, the advent of “jaywalking” was originally justified as a way to protect pedestrians; the car lobby criminalized the act in the 1920s. The auto industry funded a propaganda campaign that framed pedestrian victims as responsible for their own death after drivers hit them. Such criminalization “reconstruct[ed] how streets are used, and who they are intended for.” In other words, criminalizing “jaywalking” redefined streets from common spaces for people to gather, shop, and walk to spaces for cars to pass through.

Researchers have recently focused on the deleterious impacts of parking minimums in municipalities. Parking minimums are local laws baked into a municipality’s zoning code that mandate developers include a specified minimum number of parking spaces per new development. As cars increased in popularity, they occupied more curb space and congested streets. As a result, municipalities implemented parking minimums. These parking minimums operate under the guise of ensuring that an adequate number of parking spaces are available for cars. In reality, there are many more parking spaces than needed. Today, it’s common knowledge among parking experts that the numbers are pulled from thin airthrough arbitrary pseudoscience.

Such abundance of free parking encourages more travel by car than would parking that requires a driver to pay directly for it. This creates two inequities. First, more travel by car requires more car infrastructure, like highways from suburban areas into cities. Highways have a prickly history with racial and environmental injustice. Federal programsfacilitated highways expansion to accommodate “white flight” – that is, when White people fled to suburban areas while redlining and disinvestment stranded people of color in urban centers. This displaced low-income communities of color and elevated the risk of industrial expansion, like incinerators, in their neighborhoods. This trend of racial injustice intertwined with highway expansion persists today.

Second, free parking offsets the price of parking spaces – each costing between five and ten thousand dollars for construction alone – to the consumer. For suburbanites driving into the city, this seems fair: without free parking, they would have to pay for it anyway. But for the urbanites that live nearby or used other means of transportation, they must pay the cost for the drivers. Housing developers also pass costs of parking to tenants, adding an average of $225 per month to a tenant’s rent, according to one estimate. That is, if there’s enough land available for developers to build housing in the first place, in accordance with parking minimum laws.

Parking minimums also imperil human health. Providing “free” parking encourages passenger car use, which increases traffic, and puts pedestrians, cyclists, and motorists at higher risk of injury or death by automobile accident. Parking minimums also drive urban sprawl by the nature of needing more space for parking and encouraging developers to opt for tracts of land outside of downtowns, where prices for land run high. This can create food deserts – areas without food options – for low-income communities and communities of color. Alternatively, the urban sprawl effect can create food swamps – areas drowned by unhealthy, fast-food options – when combined with the effect that parking minimums favor national corporations over small businesses. High density of parking also takes up land that could be used for greenspaces, depriving environmental justice communities equal access to nature, in violation of Environmental Justice Principle Number Twelve.

Moreover, parking lots’ impervious surfaces exacerbate the effects of climate change and jeopardize human health. A lack of porous surfaces to absorb flood waters and carbon intensifies flooding and directly correlates with increased temperatures in urban areas. Exhaust from cars similarly exacerbates the urban heat effect. Transportation emissions are the leading contributor of direct greenhouse gas emissions in the United States. Light-duty vehicles, like pickup trucks, and passenger cars account for nearly sixty percent of these emissions. These emissions, contribute to climate change – which strains urban infrastructure – and harm human health.

The abundance of free parking that birthed car culture has robbed municipalities of robust public transportation, walkability, and bikeability – all options that are safer, release fewer emissions, connect people of all income levels to resources, and don’t require parking lots. The costs of parking outlined above are many and don’t even account for the opportunity costs of parking minimums. At the root of it all, parking minimums drive urban sprawl and perpetuate spatial injustice for lower income residents who can’t afford to live in the suburbs – or have been systemically excluded from doing so.

Cities around the United States are beginning to recognize the impacts of parking minimums and remedy their effects by abolishing such laws, instituting parking maximums, and revamping their zoning laws to include multi-use and inclusionary zoning. Reclaiming human-scale places as an equitable climate solution, however, requires keen attention to social justice. While policies that create walkable communities are inherently equitable, they also attract gentrification, the influx of wealthier demographic and development corporations displacing working class communities and communities of color due to an increase in property values. Inoculating communities against gentrification requirescollaboration among community members, grassroots community organizing, inclusionary zoning measures and proactive housing laws. Carefully un-paving parking lots could create an equitable, human-scale paradise accessible to all.