From Pollution Catastrophe to a Just and Equitable Future

By Christian Patierno

The armpit of America (as out-of-staters often refer to it), New Jersey, is working to shed this distasteful reputation with its recent groundbreaking environmental justice legislation. Some critics argue that environmental justice and job creation are incompatible, but New Jersey demonstrates that they can coexist. The two are not mutually exclusive; effective environmental regulations that protect disadvantaged communities can coexist with job preservation and creation. Despite its polluted reputation, New Jersey is making strides to create a better reality for all.

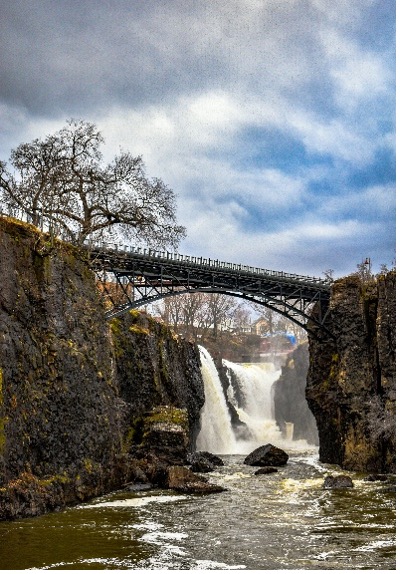

As a native New Jerseyan, I can say it is a beautiful state. Unfortunately, there are failures in the state’s environmental quality. One of the most well-known examples is the failure of the Passaic River, which was once one of the most toxically polluted rivers in the U.S. Years of manufacturing and poor disposal methods left toxins like dioxin, mercury, and PCBs, including byproducts of Agent Orange, in the sediment. This pollution, resulting from poor land-use management, negatively affects vulnerable, often immigrant populations and permeates many populated cities and towns, including my own. And New Jersey’s pollution calamity isn’t limited to rivers; ozone pollution is among the worst in the nation. According to the American Lung Association, all counties in New Jersey except for one fell into metropolitan areas that ranked among the twenty-five worst for ozone pollution. New Jersey has lived up to its reputation as a massive landfill. Of 846 landfill sites, 830 have been closed and are no longer accepting waste; however, many toxins remain and may contribute to New Jersey’s high ozone levels. Finally, driving home the pollution problem, New Jersey has the most Superfund sites in the nation, with 115 sites listed on the EPA’s National Priorities List. These sites are areas where hazardous waste has been improperly managed and are now eligible for federal clean-up funding. However, the effects of the states’ pollution are not felt equally.

The effects of these toxic pollutants are compounded by the fact that New Jersey has the highest population density of any state, resulting in increased exposure to these pollutants. They have disproportionately impacted minority communities. Many of the state’s polluted sites are clustered around major cities like Jersey City, Newark, Trenton, and Atlantic City, all of which have predominantly African American and other minority populations. Studies conducted in New Jersey indicate that many residents believe the government is not doing enough to regulate. They’ve also shown that African Americans are more likely to live in neighborhoods with poor environment and living conditions “which can limit physical activity and contribute to higher rates of premature mortality and morbidity.” This pollution can also devalue properties, create unsafe conditions, and lead to inadequate services in response. However, recent legislation has brought hope to these communities, which have been disproportionately affected by years of pollution and environmental neglect.

This legislation is underwhelmingly referred to as New Jersey’s Environmental Justice Law. However, its effects are far from underwhelming and are instead trailblazing. The law, passed by Governor Phil Murphy in 2020, requires the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) to evaluate the environmental and health impacts on overburdened communities (OBCs) when reviewing applications for new facilities. It directs the DEP to reject applications for new facilities that cannot be shown to avoid disproportionate impacts on OBCs or serve the public interest. An “overburdened community” is defined as any community in which “1. at least 35 percent of the households qualify as low-income households; 2. at least 40 percent of the residents identify as minority or as members of a State recognized tribal community; 3. or at least 40 percent of the households have limited English proficiency.” Notably, this legislation is the first of its kind in the country. It aims to provide all residents, regardless of income, race, ethnicity, or national origin, with a healthy environment to live and raise a family.

However, there’s always a “but”. Critics argue that this law, and others like it, could threaten the economy, especially in the communities it aims to protect. Ray Cantor of the NJBIA stated the rule “misses the mark by only focusing on presumed negative impacts” and doesn’t consider benefits like jobs that facilities bring. Cantor warns that communities could lose opportunities for economic development if permit decisions are made based on “the number stressors on paper, versus actual stressors.” This isn’t specific only to New Jersey; the same arguments are present at the federal level. In West Virginia v. EPA, the Supreme Court limited the EPA’s authority to regulate power plant emissions, justified by the idea that strict EPA regulations might threaten the viability of fossil fuel generation and give the EPA too much power over associated future jobs and revenue. In seeking to be shielded from regulation, the fossil fuel industry often cites the impact on revenue and potential job losses. However, justifying this by citing potential future job and revenue losses is not entirely accurate regarding environmental justice-based regulation; such regulation can support both the environment and the economy.

On a national level, the Inflation Reduction Act has led to billions being invested in clean energy and climate resilience. The Inflation Reduction Act, at the same time, while it works to combat pollution, has generated numerous new jobs. Examples include BlueOval SK, a subsidiary of Ford funded by the IRA, which will build battery manufacturing plants and create 7,500 new jobs near disadvantaged communities. Another employer, ChargerHelp! is training thousands of maintenance technicians from disadvantaged communities to support EV expansion. Yet another, BlocPower, installs low-infrastructure Wi-Fi networks and other electric technologies in low-income neighborhoods. Under the IRA, it also makes certain tax rebates available to customers. EJ policies are not holding these businesses back; they are helping them. Companies are learning to align with federal and state initiatives and secure funding to support communities in need. Environmental attorney Matthew Karmel notes that even in New Jersey, where regulations are stringent, companies are taking proactive measures, engaging with the community, conducting risk assessments, and considering the proximity of EJ communities when evaluating a project.

The New Jersey Environmental Justice Law is not anti-economy; it’s meant to protect disadvantaged communities. The law requires companies to demonstrate that they cannot avoid disproportionate impacts on disadvantaged communities, and if they cannot, they must take additional measures to protect those communities facing greater burdens. This is more than strict permitting; it gives a voice to disadvantaged communities. It helps demonstrate that environmental regulation can have a positive impact on economic growth and that growth doesn’t need to harm public health, especially in disadvantaged communities, while providing good access to jobs.

New Jersey is taking a strong stance with its law, even if a new facility would greatly boost the economy. If it negatively impacts a disadvantaged community, the project should and will be dead in the water, or, I suppose, the Passaic. For a long time, disadvantaged communities in New Jersey have been subjected to pollution by companies that disregarded their health. The law seeks to strike a balance between the two, favoring disadvantaged communities and their health while also providing jobs. One of the most polluted states is making progress. If New Jersey can do it, so can others.