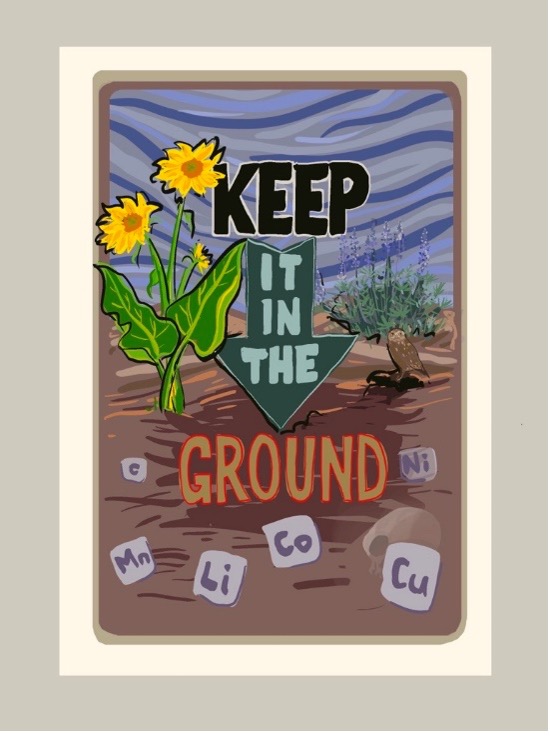

image used with public share permission from: ProtectThackerPass.org/resources

While We’re Here: Acknowledging Harm in Federal Green Initiatives

By Ariana Richmond

On day one in office, the new administration canceled climate change initiatives. Executive Order 14154 eliminated the “electric vehicle (EV) mandate,” revoked twelve executive orders addressing the climate crisis, and attempted to override bipartisan climate change legislation. Setting aside the consequences likely to result from an absence of federal leadership, this complete stop is also an opportunity to pause and think about equitable solutions through a Just Transition. To that end, how have green initiatives like electric vehicle goals harmed marginalized communities?

Federal green initiatives—even well-intentioned with environmental justice—too often still come at the expense of historically oppressed communities. Under the Biden administration, there was bipartisan support for clean energy and infrastructure as well as environmental justice—and even for putting them all together.

At the executive level, the Biden administration committed to environmental justice through the Justice40 (J40) Initiative. Through Executive Orders 14008 and 14096, the White House committed 40% of overall benefits from federal clean energy and infrastructure projects to historically disadvantaged communities.

Consistent with this, Congress passed, and President Biden signed into law, two pieces of landmark legislation: the 2021 Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (commonly known as the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law or BIL) and the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act (IRA). Both laws established infrastructure and clean energy projects that prioritized disadvantaged communities. From this, the Biden administration produced a list of over 500 programs under J40authorized by Congress for climate change and environmental justice. In this way, the federal government committed to a green economy while purporting to serve marginalized communities.

However, some of the clean energy programs directly harm marginalized communities. For example, the BIL and IRA advance electric vehicle (EV) manufacturing, which has harmful local impacts. The IRA alone appropriated $3 billion to the Department of Energy’s Advanced Technology Vehicles Manufacturing Loan Program, and removed the program’s loan cap, to fund direct loans for manufacturing facilities for EV battery critical minerals. Accordingly, the Department of Energy issued a $2.26 billion loan to Lithium Americas, a Canadian company, to build a lithium mining facility at Thacker Pass in northern Nevada. Notably, this is all part of the J40 environmental justice program. Further, both the Biden and previous administration supported the mine, with the Biden administration increasing funding and finalizing the loan.

The area of the mine, Thacker Pass, Nevada (Peehee Mu’huh), is unceded land. The Numu/Nuwu and Newe Peoples maintain rights to the land. Today, the area borders Oregon, sits atop an extinct volcano, and is likely one of the largest sources of lithium in the U.S. Most importantly, the area is hugely significant to the Indigenous Peoples who have lived there since time immemorial.

Forcibly removed to reservations nearby, at least six federally recognized Tribes of the Numu/Nuwu and Newe People resist the mine site. The Fort McDermitt Paiute and Shoshone Tribe has a 54-square mile reservation that is around 30 miles from the mine. Some of the harm to Tribes from the mine includes: obstructing hunting, fishing, and gathering rights; preventing cultural and religious practices; obstructing the continuation of traditions; and infringing on ancestral land claims—in addition to ecological and environmental harm. There is also an increased risk of violence, including sexual violence against women, historically pervasive among extractive industry practices. Additionally, the land is a sacred burial site since 1865, when U.S. soldiers massacred Numu/Nuwu and Newe Peoples who inhabited the land.

Tribes resisting the mine have sued in federal district court, lost, and lost on appeal at the Ninth Circuit. Under the National Historic Preservation Act and NEPA, the federal government must follow procedural requirements, including Tribal consultation, before approving the project. Additionally, the U.S. government has a trust relationship with Indigenous Nations and must engage in good-faith, nation-to-nation consultation. According to a February 2025 Human Rights Watch report, the construction of the mine also violates Indigenous Peoples’ rights under international law, to obtain free, prior, and informed consent before permitting the mine. Yet, the U.S. government failed to uphold each of these obligations.

In this way, the lithium mine violates the rights of Tribes despite the U.S. government categorizing the project as green and just. This case illustrates how federal green initiatives purporting to advance environmental justice fail to do so. A green economy carried out at the expense of Indigenous Peoples is neither green nor just. It is important to acknowledge this harm now while federal initiatives are stalled. It is equally important to consult directly with environmental justice communities, including Indigenous Peoples, before advancing policies for a green economy.